An exact force is needed in order to perform well in putting

- Dr David Moffat

- Jul 7, 2021

- 9 min read

Updated: Jul 31, 2021

Putting requires the golfer to regulate motor and force control to optimise their actions. The ability to adjust muscle strength precisely is an important factor for the putting movement. In particular, it is difficult for golfers to apply small amounts of force precisely due to the challenging nature of applying the requisite degree of fine motor control. So, how do we learn how to impart the correct amount of force to get the ball to the hole? Let’s start with some insight into motor learning for force control and a basic understanding of how the brain helps improve your putting.

Motor learning is associated with systematic changes in proprioception (i.e., perception or awareness of the position and movement of the body). Elite golfers (e.g., Jordan Speith and Tiger Woods) exhibit a finer degree of awareness of the position and movement of the parts of the body than most golfers. I suggest this can be explained by their cerebellum (Latin for little brain) being more efficient and proficient than most.

Neural efficiency reflects 2 different processes in distinguishing elites from experts and novices: 1. A reduction in neural activity in certain brain regions as a skill becomes automated and less controlled; 2. A reduction of activity in sensory and motor cortex, reflecting more efficient processing by less energy expenditure.

The cerebellum may be small but it contains about 70 billion neurons (5 times as many neurons as the larger cerebral cortex) and takes centre stage in its importance when it comes to honing our practical putting talents. The cerebellum helps improve motor skills by detecting errors in the clubface, putting stroke movement, force control and making minute adjustments to the next putting stroke. These adjustments strengthen the connections within neural circuitry encoding the complex movement. In other words, the cerebellum helps you improve your putting when you employ a structured practice routine.

Elite golfers are able to fine-tune their force output because of their long-term structured practice regimes that refined schemas (i.e., perceptual kinetic experience) resulting in more appropriate parameter settings regarding force, magnitude, and duration of the putting stroke. Indeed, elite golfers need continuous practice to be able to keep the duration of the downswing constant. This indicates that most club golfers have to spend a great deal more time learning how to regulate the force of the putt.

Interestingly, what the research suggests is that elite golfers must learn to regulate the putting force by varying the distance of the backswing, keeping the duration of the downswing constant, indicating that the distance was more important than the duration. Moreover, elite golfers could actually be said to use a kind of scaling when putting. That is, if the distance to the hole is judged to be short they try to make the backswing short and with a longer distance to the hole they try to adapt by attempting a longer backswing.

The relationship between the distance and length of the putting stroke can be described quantitatively by utilising psychophysical scales. I suspect most club golfers may not be aware of the scaling aspect, nor of the quantitative relationship. These scales vary in complexity, from simple ones with numbers at equal intervals, to more complex ones with categories functioning as verbal anchors.

Let me explain, psychophysical scales provide ratio data that provides a more true description of the relationship between the subjective and physical realities. This is of great advantage to golfers because we act and react according to how we perceive the world rather than to how the world actually is. Moreover, using ratio data, more advanced statistical methods can be used. For example, this means that if the distance to the hole is doubled the force needed will be more than twice as great. If power functions are calculated predictions can be made as to the force needed for a certain distance. The exponent of the power function is sensitive to changes in the putting-task conditions, thus providing you with important information for improvement.

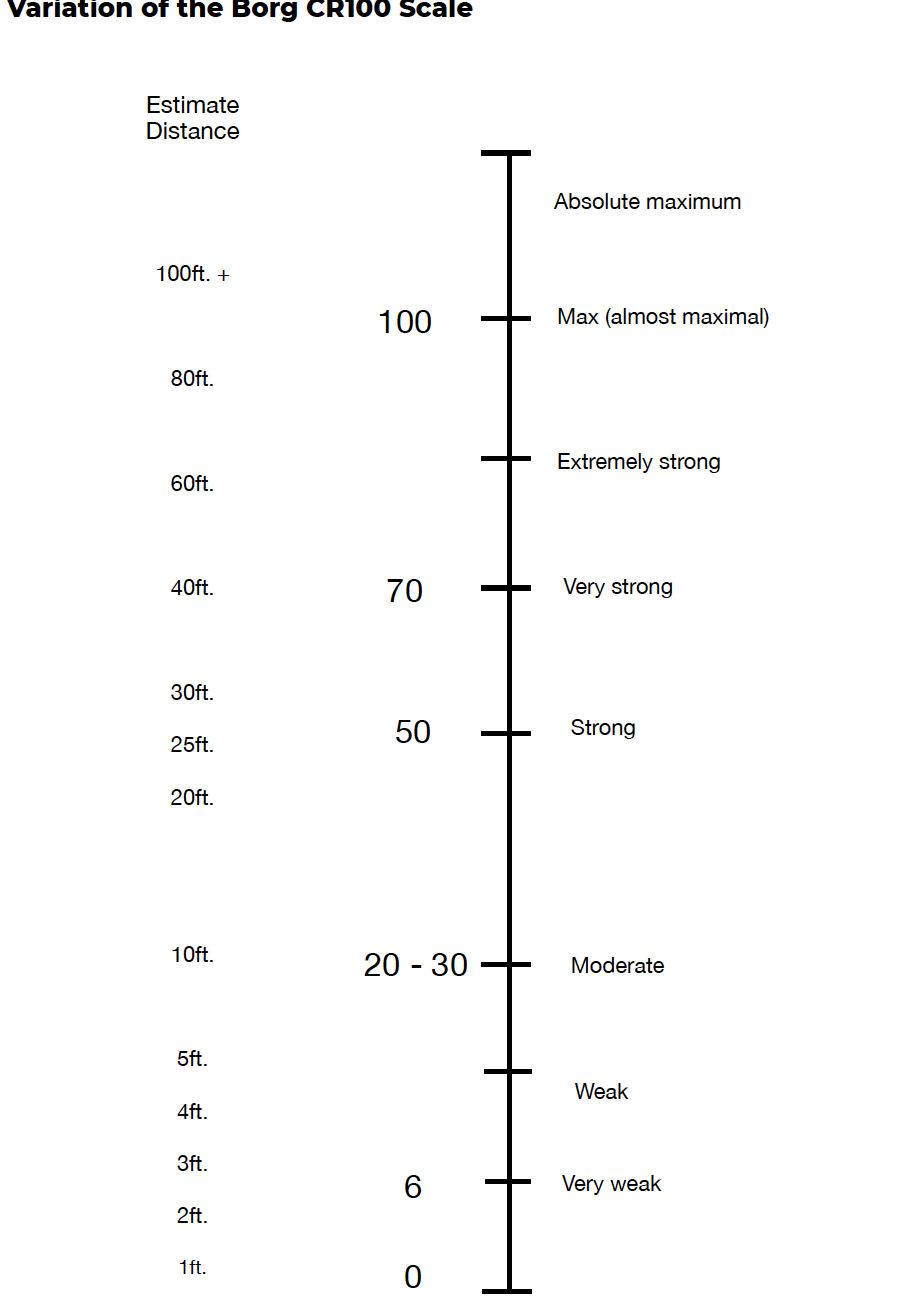

I employ a variation of the Borg CR100 Scale, as this particular scale is very well suited for putting. The letters CR stand for category and ratio, as the scale combines categorical verbal anchors with a numerical ratio scale. The verbal anchors, carefully chosen and tested, are placed along the scale at positions that are natural and consistent with a ratio scale. To reduce the risk of verbal anchors being misinterpreted I use expressions or words that are easily understood and experienced by golfers. For example, I use the following anchors - very weak, weak, moderate, strong, very strong and extremely strong, thus describing a variation in force. One advantage of this type of scale is that it makes it easier for the golfer to choose the right intensity, compared to simple numbers.

As illustrated below the scale numerically covers the subjective range from 0 (nothing at all) to 100 (maximal), thus providing a measurement in intensity in centigrade of a maximal experience. The maximal experience is the most important anchor on the scale. According to the range model, it is assumed that the range of subjective intensity judgements from 0 to maximal is equal for different persons even if the physical stimulus intensities may differ. An example of this is one golfer having previous experience of much longer distances to holes when putting than another golfer (e.g., playing regularly at St Andrews with large double greens), or that the two golfers may differ in muscle strength. Both golfers are then supposed to use the same range from 0 to maximal, but the actual force needed for maximal is likely to be different for the two of them. Thus, when you are using the scale, a great focus should be placed on defining the maximal levels, especially 100 “maximal” as this is the main anchor and reference level.

Use this scale to decide how strong your putting experience is. The strongest putting force you have ever experienced should be set to the number 100. This is a very important level and serves as a point of reference in the scale. The scale works like a scale of percentage and there is very good accordance with the meaning of the words in the scale and what the numbers stand for. First, look at the verbal anchors. Start with one of them and choose a number close to that expression. If your experience and feeling of the force needed are “very weak,” choose a number around 6. If your experience is “moderate” choose a number between 20 and 30. Remember that “moderate” is about 25, and thus weaker than the middle (50) of the scale. If your experience is “strong” the corresponding number is around 50; that is, 50% of what is supposed to be the maximum (Max) on the scale. If your experience is “very strong,” choose a number around 70. Use whole numbers only. It is very important that you choose a number representing what you actually feel in the putting situation and not what you believe is the proper number to use.

In addition to the above instructions, you must determine what situation is “max” for you, as this level is important for the ratings to be reliable. For using the scale in practice I recommend that you register the distance for each putt and its corresponding scale value (e.g., 85) and expression (e.g., ‘extremely strong’). This procedure should be repeated several times for each distance.

Guidelines for Applying the Borg CR100 Scale in Practice

Choose one of the verbal anchors on the scale and produce a putt corresponding to what you feel is the force meant by this expression. You may start with any anchor you want, a tip is to randomly start with different anchors

2. Measure the distance of the putt with a measuring tape or step it out

3. Register the verbal anchor expression, the scale value and the value of the distance in a table for future use

4. Proceed in the same way with other scale values and anchor expressions, chosen from all along the scale up to max

The guidelines shown above are suggested for each skill level. It is assumed that the practice takes place on the practice green and that the scale instructions have been studied and understood. Also, you should try to find a place to practice “maximal” putts. In this way, the intensity of the anchors such as “weak,” “strong,” and “very strong,” and their positions in the total subjective range, with “maximal” as a main important conception will be more distinct and the anchors themselves will; be easier to use. Upon finishing practice for the day, it is recommended to calculate the mean of the distances for each of the scale values and verbal anchors practiced up to then. As there is always some variation in making a putt; the means are likely to be the best values for predicting the present skill.

Measuring Distances

Distances should be measured with a measuring tape to ensure acceptable relationships between scale ratings and distances. Alternatively, it is also wise to practice some other means of determining the distance to the hole, such as judging the distance visually, or counting steps between the position of the ball and the hole, and then comparing these measures with a measuring tape. The step method is preferable as it is likely to have results close to those of the measuring tape method. Furthermore, it is helpful to practice visually judging ball distances now and then. This type of practice is especially important with uphill putts as an uphill slope can cause an underestimation of the real distance and the force needed to reach the hole.

It is likely that weather conditions can change the speed of the ball from time to time, creating variation in the distances obtained for a certain scale value. If possible, the scale should be practiced under comparable conditions, at least until it is well understood and you feel confident with the variation in distances that will be obtained for a given scale value or anchor. With practice, more factors contributing to the distance of a putt can be taken into consideration, and you can move to a routine as the one suggested below for the preparation of a round.

Pre-Round Calibration Procedure

Preparation before each round for judging force on the course requires a calibration procedure. A straightforward way to do this is to bring a copy of the scale to the practice green the day of play, find a flat area on the green and note on the scale how many walking steps the ball will roll for various verbal descriptors or numerical values of the scale.

Follow this calibration procedure:

1. the golfer determines what force is associated with the chosen verbal anchor or scale value

2. holes the putt

3. finishes by counting the steps to the ball

It is very important never to change the place of the anchors and values printed along the scale as this will invalidate the scale’s properties. Thus, the distance the ball will roll varies with surface, weather conditions and so forth, but the force as defined by the verbal anchors should remain the same.

During the calibrating procedure on the practice green, it could be wise to make several putts for each verbal descriptor in order to obtain a more stable estimation of the actual distance for the descriptor. Then, while playing on the course, you only need to measure the distance by counting the number of steps on the green from ball to hole and make the putt in accordance with the force indicated on the scale suitable for that distance. Should there be strong deviations from the conditions on the practice green, you must make appropriate judgements for adjusting the force of the putt. With practice, the scale will be used more comfortably in deviating conditions and you will increasingly use its numbers for regulating the force of the putt.

In conclusion, there is useful knowledge to be gained from the field of psychophysics. In this blog, I have demonstrated that the modified Borg CR100 Scale can be used to increase putting skill for golfers of varying handicaps and experience. A golfer friendly procedure is suggested for how the scale can be used during practice and in competition, including specific instructions for preparing to use the scale before a round. It is also suggested that by calculating psychophysical functions and exponents, you can obtain valuable information to be used in predictions of force and how force may vary for different golfers under different playing conditions, such as during practice and in stressful situations during competitive rounds. Additionally, the use of this tool may reduce stress by helping you stick to a rule for what force to apply in any given putting situation as part of your pre-putt routine.

To hammer home this point, it seems there is much more putting instruction focusing on teaching how to maintain a correct line to the hole rather than on regulating the force needed to reach the hole. As golfers, we accept it is not easy to keep the ball on the correct line and we should practice this task regularly. However, I would argue that for most skill levels it is more difficult to gauge the amount of force than it is in direction. Therefore, I suggest a better strategy for putting practice would be to increase attention to the precision of distance to the hole rather than the precision of direction to the hole.

Go practice and MAY THE FORCE BE WITH YOU!